Roshanak Keyghobadi | January 2015

Typography has been identified in a number of ways and its definition has gone through changes throughout the history of design based on aesthetic, cultural, social and technological ideas and transformations.

Friedrich Friedl, Nicolaus Ott and Bernard Stein (1998) in their book Typography: An Encyclopedia of Type Design and Techniques Throughout History state: “the 20th century brought change to all areas of art and culture. The legacy of past centuries was consciously forgotten to make way for the new. Art saw the transformation from representational to abstract painting. Unfamiliar images were greeted with vehement enthusiasm and rejection alike before they were accepted as an expression of a society under radical change. This in turn changed ideas of harmony, form and proportion. Typography, which had changed little since Gutenberg and then only in conformity with a rigid pattern of rules, was also embraced by these new concepts. In the past it had been a steady medium which served reading and writing; now suddenly began to move.”(p. 8)

Rob Carter, Ben Day and Philip Meggs (2002) in Typographic Design: Form and Communication also highlight the changes in the function and definition of typography since the early twentieth century. They explain: “the typographic message is verbal, visual, and vocal. While typography is read and interpreted verbally, it may also be viewed and interpreted visually, heard and interpreted audibly. It is a dynamic communication medium. In this sense, early twentieth- century typography becomes a revolutionary form of communication, bringing new expressive power to written word.” (p. 74)

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1923) in his essay titled “The New Typography” explains: “epigraphy is a tool of communication. It must be communication in its most intense form. The emphasis must be on absolute clarity since this distinguishes the character of our own writing from that of ancient pictographic forms” . In 1971 designer Herbert Bayer describes typography as “a service art, not a fine art, however pure and elemental the discipline may be.”

Later Philip Meggs (1992) clarifies that, traditionally, the word typography meant the technical process of printing writing through the use of metal types with raised letterforms that could be linked and printed in a process not unlike a rubber stamp. In our electronic age, typography encompasses the transmission and communications of alphabetical and numerical information through a variety of means, including printing, video transmission, computer display, and electric signs. What Meggs is describing is the evolving nature of typography and its essence and meaning. In a sense typography is no longer about the metal type or typeset matter but it is as James Craig and William Bevington (1999) explain, “the art of designing with type.”

Also, Kees Broos (1982) in the essay “From De Stijl to New Typography” proposes: “let us define the word “typography” here as the deliberate use of letters, in the broadest sense of the word. The user can be printer, typographer, architect, poet or painter. The materials are not restricted to those of the type case or typesetting machine, but encompass every suitable medium from linoleum to electronic news marquees and from a tile tableau to television. It is important that the user be aware of the shape and function of each letter and consequently of the expressive potential in the design and arrangement of letters and text opened up to the reader and the viewer.”

The definition of typography and the space that it creates for layers of meaning and interpretations are continually expanding and shifting. As Rick Poynor (1991) in his essay “Type and Deconstruction in the Digital Era” explains: “contemporary typographic works embody multiple readings, encourage readers’ participation and are becoming complex.” Poynor states: “type design in the digital era is quirky, personal and unreservedly subjective. The authoritarian voices of Modernist typography, which seem to permit only a single authorized reading, are rejected as too corporate, inflexible and limiting, as though – it may be forlorn hope – typographic diversity itself might somehow re-enfranchise its readers…The aim is to promote multiple rather than fixed readings, to provoke the reader into becoming an active participant in the construction of message. Later Modernist typography sought to reduce complexity and to clarify content, but the new typographers relish ambiguity, preferring the provisional utterance, alternative take, and delayed punchline to finely honed phrase.”

Jessica Helfand (1995) in her essay “Electronic Typography” draws the attention to the performative and dramatic nature of contemporary typography and asks: “What happens when written words can speak? When they can move? When they can be imbued with sound and tone and nuance and decibel and harmony and voice? As designers probing the creative parameters of this new technology, our goal may be less to digitize than dramatize.”

Another factor that influences the evolving definition of typography is who is defining it and in what cultural context it is defined. For example the complexity and openness of the definition of typography sometimes creates anxiety and unease among artists and designers.

Currently in the Iranian design scene one of the heated topics of conversation and criticism is typography and its definition. Although typographic activities such as siyah mashq (even if they are not recognized as typography) have long been practiced in Iran, yet typography is confronted as a new phenomenon that is overpowering every aspect of the graphic design. In 2006 Ebrahim Haghighi (2006) in his essay titled “Poster Mania” puts forward several questions about “the emergence of a new form of art called typography.” He states: “it is not clear whether it is painting or sculpture, graphic design or photography, cinema or video art. It may encompass all or may be independent and self sufficient with its own set of principles and techniques. Does every work produced by calligraphy, penmanship or fonts classify as typography? How can we distinguish that it is not a work of graphic design or painting? By which rule or principle has this new labeling been defined? ”

Other Iranian designers have expressed their understanding and definition of typography as well. Morteza Momayez (2004) explained: “typography is not merely the design of the letters. In today’s world there are a number of different definitions for typography. We cannot even say that typography is design with script or letters, because in some instances in the hands of a typographer or type designer or a layout artist, it creates an atmosphere that visualizes the written concepts.”

Mohammad Ehsaei (2010) separates writing and calligraphy from typography and explains: “when we say typography, at once typing letters come to mind. You are typing the letters that have been pre-designed for specific needs and goals. Delicate letters are designs for delicate concepts and rough letters for bolder purposes…Therefore we have typography, calligraphy and writing. Each has a different function, form and aesthetics. Nowadays all of these are presented in form of what is called a font and the common mistake is to call all of them typography. Calligraphy can never become a font. A calligrapher sits down and creates a calligraphic work and if a nastaliq font is designed it is not calligraphy anymore. When a letter or a word is designed for a logo and is not going to be used for other typesetting purposes, it is not called typography. For example when you look at Herb Lubalin’s Mother and Child logo it is not typography it is graphic design…Calligraphy is the mastery and skill that is embedded in calligrapher’s hands and anything that the calligrapher creates on the paper is personal and would be for the first and last time; just like writing.”

In his essay titled “What is typography?” Saed Meshki (2004) states: “the most important, and at the same time, the most challenging function of typography is to create by letters and words an ambiance capable of conveying to the viewer something of the essential character of the subject, and also something of the graphic designer’s feelings about the subject and his or her grasp of it. Letters and characters are a set of signs that by virtue of their familiarity impart to the viewer something more than just an exercise in pure form even if they are not legible in a typographic composition. Because of their characteristic shapes, Persian letters and words are imbued with energy of their own. It is by the correct exploitation of this latent energy of Persian letters and by discovering the aesthetic criterions that apply to them that Persian typography is distinguished from Western typography.”

Reza Abedini (2010) defines typography as: “any activity by a graphic designer to give letters and writing a visual meaning beyond information…There is a major problem with trying to define typography. When you ask what is the definition of typography it is like asking what is the definition of computer, and in addition you want to know what is Iranian typography? There is no such thing. If we want to talk about computers, Iranians have no role in its creation. They may like to translate its name to Persian and call it Pardazeshgar to feel better but this does not change anything about the nature and function of the computer. Well, it is the same story with typography. Basically typographic activities are meaningful in Western visual art specifically in Western graphic design…What I mean is if I want to be seriously working on Persian calligraphy and Persian letters it is not necessarily called typography anymore. Using computer as an example again, I should create a device, which can solve my [an Iranian person] problem, because computer has solved the problem of a Western person.”

Masoud Nejabati (2004) stated: “in my view typography is giving sensitivity to letters. If we agree that every graphic design work is made of two basic elements of type and image, the quality and validity of what is written is based on typography. Which means that type has been changed from its usual form. If letters are endowed with sensitivity then a typographic work is created either in concrete form or abstract form.”

Homa Delvaray (2010) states that: “typography has a wide definition and I can not fit it in one sentence, but what comes to my mind is when we consider specific qualities of letters in a work and emphasize that aspect it becomes typography. It is in reality a graphic design style, which people choose to use and it can be objective or subjective. If they look at typography objectively, they transfer the meaning by objective means and if they chose to use is subjectively and in abstract context, they use letters as codes. It all depends on the designer’s taste…When we concentrate on each letter and position them in a space in order to create a composition, it becomes a typographic work.”

In conclusion, I believe that the most contemporary and relevant description of typography is what design critic and educator Ellen Lupton has put forward which is “the art of designing letterforms and arranging them in space and time.” Lupton (2000) explains: ” Typography is going under water as designers submerge themselves in the textures and transitions that bond letter, word, and surface. As rigid formats become open and pliant, the architectural hardware of typographic systems is melting down.”

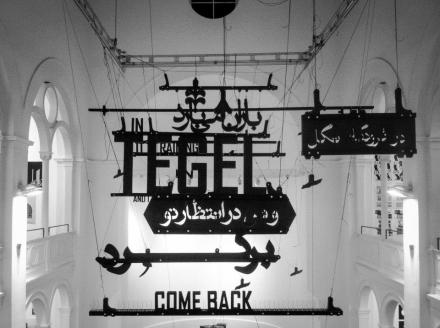

Artworks by: Shahrzad Changalvaee, Reza Abedini, Farhad Fozouni, Homa Delvaray, Iman Raad and Mohammad Ehsaei.

© Roshanak Keyghobadi, 2015. This essay cannot be reproduced, quoted, translated or published in part or as a whole in any format without Roshanak Keyghobadi’s permission.